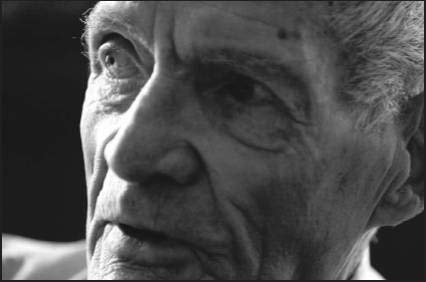

Profile of Art Tremayne, Mount Pisgah Caretaker

Caretaker lovingly tends cemetery in Cripple Creek

Council will discuss burial ground’s future

By DeeDee Correll, The Gazette, Colorado Springs, Sunday, February 20, 2005, Metro pages 1 and 3

Art Tremayne knows everybody at Mount Pisgah Cemetery.

There’s Avis, who once worked in the kitchen of his restaurant, until he fired her for not showing up.

There’s Mr. Brandt, who built a wagon Tremayne’s dad used on his milk route.

Here’s Les the butcher, and the rest of his kin. Tremayne knew most of them, too.

“Everyone buried here since 1928 — I knew most all of ’em,” said the 87-year-old caretaker.

He knew them in life, and he knows them still, crisscrossing every day between their graves, trimming the weeds, setting up headstones trampled by elk, guarding them against vandals.

The only thing Tremayne doesn’t do much anymore is sell plots.

People aren’t dying in Cripple Creek these days.

The gaming workers are too young. The old have died or moved. The bottom line is that Mount Pisgah isn’t paying for itself because no one’s shelling out $1,000 for the right to spend eternity here.

Now Tremayne’s hometown faces a decision: Should it close its cemetery?

If it does, Tremayne will be OK.

He’s got his plot in the Masonic section, where his beloved Loretta waits. She went in October, of pneumonia.

That she’d make the trip to Mount Pisgah before he did was a surprise, but he’s trying to adjust.

“I stop by here every morning and every night,” he said.

Someday, he’ll stay. He’s had the headstone made with everything engraved but the year of his death.

So he’s OK, but what about the others? “I can’t figure a town that don’t have a cemetery,” he said.

***

At 8 a.m. every day, Tremayne slides the lock off the wrought iron gate and opens Mount Pisgah.

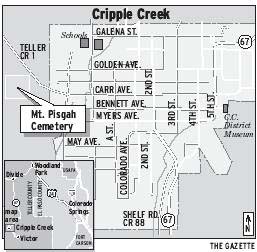

The cemetery sits west of town, down Teller County Road 1, away from the casinos. Its 35 acres roll up a hill dotted with jackpines and aspen; at the top, Tremayne can see all of the town where he was born.

His grandpa — buried here along with his grandma — was a county commissioner. His dad, resting under bouquets of plastic roses near Loretta, worked in the Cresson Mine.

Tremayne became a miner, too, making $4.25 a day. He also tended bar, selling shots of whiskey for 25 cents and losing track of the brawls. He ran a machine shop and the Cottage Inn restaurant and was on the City Council twice, once as mayor and once as mayor pro tem.

Occasionally, his neighbors went to Mount Pisgah, and Tremayne went to see them off.

The cemetery already was full of people who died at the turn of the century, when the city had a population of more than 25,000. But many of their names were lost as headstones eroded or disappeared. In the 1950s, the mortuary burned down, destroying all the burial records.

As the years passed, Mount Pisgah drowned in weeds.

Then came the 1990s and gaming. Cripple Creek got some money for historic preservation and decided to use it to spruce up the cemetery. The city advertised for a caretaker, and Tremayne, then in his late 70s, got the job.

“There was weeds and grass this high,” Tremayne said, his hand at his waist.

Tremayne still has a full head of carefully combed white hair. He speaks steadily and drives a car. He might not do things as fast as he once did, but he manages to do them, with some help from a hired man: run a lawnmower, move rocks, paint fences.

One of the first things he did was mow down the grass.

He leveled crooked headstones and dug out the ones sunk in the ground. He repainted fences and searched for the cemetery’s many unmarked graves, studying places where the earth has sunk low or mounded too high.

“I’ve found 1,200 so far,” he said. “I’m not finished yet.”

He’s not finished either with the resident badger, who’s taunted him by digging holes among the graves.

Once, the critter dug clear down to a casket, ripped the handle off and pulled out a bone. Tremayne called the game warden.

“She said, ‘Go ahead and waste him,’” he said. Tremayne brought his gun to work, but hasn’t seen the badger since.

After nearly 10 years, Tremayne knows Mount Pisgah like his own house.

When someone shows up looking for a particular grave, he can take them straight to it. He’s made a list of every one and where to find it. Why this is important couldn’t be more obvious to him.

“A cemetery is a museum of your city,” he said.

A key figure in that museum is Pearl DeVere, a madame who died in 1896 and whose headstone is draped with the trinkets people leave for her — Mardi Gras beads, lipstick and cans of Coors. Once someone left a $10 bill. Tremayne glued it to the top of the headstone so it wouldn’t blow away.

What is, he believes, should stay that way.

***

Mount Pisgah will stay.

There’s no question of that — only of whether the city will keep using it.

Tremayne was the one who raised the issue. He wanted some rules about who was allowed to be buried there. Should a resident pay the same amount as someone who hasn’t lived there? Should the cemetery bury nonresidents?

The general rule now is that residents pay the same as nonresidents — $1,000 — if they buy a plot in advance. If residents die without buying ahead of time, they’re buried for free, but the city picks the spot.

As the Cripple Creek City Council considers these matters, it must ask the bigger questions about Mount Pisgah’s future, historic preservation director Larry Manning said.

“The city has to decide if it wants to stay in the cemetery business,” he said.

Mount Pisgah hasn’t had more than 30 or 35 burials in the past 10 years.

The city’s population is about 1,200 now, and the median age of its residents is 38. Only 89 residents were over the age of 65 at the time of the 2000 census.

Manning knows the cemetery means a lot to some people — those who grew up here and expect to be buried in Mount Pisgah.

The council will weigh that, as well as the cost of running the cemetery — $35,000 a year, all of which is subsidized by the city. Before the council makes any decision, Manning said he’ll suggest the city seek reaction from residents.

Colorado Springs’ two cemeteries pay for themselves through the sale of plots, making them the only two of their kind in the country, cemetery manager Will DeBoer said.

Cemeteries close all the time because they run out of space, DeBoer said, but that’s not always a bad thing; people can still visit them.

“The history doesn’t go away,” he said. “What you lose is the ability to bury a couple of generations in that cemetery.”

To some in Cripple Creek, that would be no small loss.

Laura Jeffery, 76, isn’t sure whether she wants to be buried or cremated. Either way, she hopes Mount Pisgah doesn’t close its gates to burials.

“It’s important for the history of the area that it stay open,” said the 30-year resident.

That’s especially true now that the city is starting a push to attract tourists based on history, she said.

As for Tremayne, he’s got unfinished business.

One day, he made a list of the things he’d like to see: the cemetery’s dirt roads named after the people who made the town what it is; replacing his wood markers on the graves of the unknown with metal ones so they’ll last forever; finding the rest of the hidden graves.

Most of all, Tremayne wants to be there every morning to open the gates and again at 5 p.m. to lock them.

He loves this cemetery, after all, and taking care of it keeps him from thinking about how much he misses his wife.

“It’s what keeps me going.”

Caretaker lovingly tends cemetery in Cripple Creek

Council will discuss burial ground’s future

By DeeDee Correll, The Gazette, Colorado Springs, Sunday, February 20, 2005, Metro pages 1 and 3

Art Tremayne knows everybody at Mount Pisgah Cemetery.

There’s Avis, who once worked in the kitchen of his restaurant, until he fired her for not showing up.

There’s Mr. Brandt, who built a wagon Tremayne’s dad used on his milk route.

Here’s Les the butcher, and the rest of his kin. Tremayne knew most of them, too.

“Everyone buried here since 1928 — I knew most all of ’em,” said the 87-year-old caretaker.

He knew them in life, and he knows them still, crisscrossing every day between their graves, trimming the weeds, setting up headstones trampled by elk, guarding them against vandals.

The only thing Tremayne doesn’t do much anymore is sell plots.

People aren’t dying in Cripple Creek these days.

The gaming workers are too young. The old have died or moved. The bottom line is that Mount Pisgah isn’t paying for itself because no one’s shelling out $1,000 for the right to spend eternity here.

Now Tremayne’s hometown faces a decision: Should it close its cemetery?

If it does, Tremayne will be OK.

He’s got his plot in the Masonic section, where his beloved Loretta waits. She went in October, of pneumonia.

That she’d make the trip to Mount Pisgah before he did was a surprise, but he’s trying to adjust.

“I stop by here every morning and every night,” he said.

Someday, he’ll stay. He’s had the headstone made with everything engraved but the year of his death.

So he’s OK, but what about the others? “I can’t figure a town that don’t have a cemetery,” he said.

***

At 8 a.m. every day, Tremayne slides the lock off the wrought iron gate and opens Mount Pisgah.

The cemetery sits west of town, down Teller County Road 1, away from the casinos. Its 35 acres roll up a hill dotted with jackpines and aspen; at the top, Tremayne can see all of the town where he was born.

His grandpa — buried here along with his grandma — was a county commissioner. His dad, resting under bouquets of plastic roses near Loretta, worked in the Cresson Mine.

Tremayne became a miner, too, making $4.25 a day. He also tended bar, selling shots of whiskey for 25 cents and losing track of the brawls. He ran a machine shop and the Cottage Inn restaurant and was on the City Council twice, once as mayor and once as mayor pro tem.

Occasionally, his neighbors went to Mount Pisgah, and Tremayne went to see them off.

The cemetery already was full of people who died at the turn of the century, when the city had a population of more than 25,000. But many of their names were lost as headstones eroded or disappeared. In the 1950s, the mortuary burned down, destroying all the burial records.

As the years passed, Mount Pisgah drowned in weeds.

Then came the 1990s and gaming. Cripple Creek got some money for historic preservation and decided to use it to spruce up the cemetery. The city advertised for a caretaker, and Tremayne, then in his late 70s, got the job.

“There was weeds and grass this high,” Tremayne said, his hand at his waist.

Tremayne still has a full head of carefully combed white hair. He speaks steadily and drives a car. He might not do things as fast as he once did, but he manages to do them, with some help from a hired man: run a lawnmower, move rocks, paint fences.

One of the first things he did was mow down the grass.

He leveled crooked headstones and dug out the ones sunk in the ground. He repainted fences and searched for the cemetery’s many unmarked graves, studying places where the earth has sunk low or mounded too high.

“I’ve found 1,200 so far,” he said. “I’m not finished yet.”

He’s not finished either with the resident badger, who’s taunted him by digging holes among the graves.

Once, the critter dug clear down to a casket, ripped the handle off and pulled out a bone. Tremayne called the game warden.

“She said, ‘Go ahead and waste him,’” he said. Tremayne brought his gun to work, but hasn’t seen the badger since.

After nearly 10 years, Tremayne knows Mount Pisgah like his own house.

When someone shows up looking for a particular grave, he can take them straight to it. He’s made a list of every one and where to find it. Why this is important couldn’t be more obvious to him.

“A cemetery is a museum of your city,” he said.

A key figure in that museum is Pearl DeVere, a madame who died in 1896 and whose headstone is draped with the trinkets people leave for her — Mardi Gras beads, lipstick and cans of Coors. Once someone left a $10 bill. Tremayne glued it to the top of the headstone so it wouldn’t blow away.

What is, he believes, should stay that way.

***

Mount Pisgah will stay.

There’s no question of that — only of whether the city will keep using it.

Tremayne was the one who raised the issue. He wanted some rules about who was allowed to be buried there. Should a resident pay the same amount as someone who hasn’t lived there? Should the cemetery bury nonresidents?

The general rule now is that residents pay the same as nonresidents — $1,000 — if they buy a plot in advance. If residents die without buying ahead of time, they’re buried for free, but the city picks the spot.

As the Cripple Creek City Council considers these matters, it must ask the bigger questions about Mount Pisgah’s future, historic preservation director Larry Manning said.

“The city has to decide if it wants to stay in the cemetery business,” he said.

Mount Pisgah hasn’t had more than 30 or 35 burials in the past 10 years.

The city’s population is about 1,200 now, and the median age of its residents is 38. Only 89 residents were over the age of 65 at the time of the 2000 census.

Manning knows the cemetery means a lot to some people — those who grew up here and expect to be buried in Mount Pisgah.

The council will weigh that, as well as the cost of running the cemetery — $35,000 a year, all of which is subsidized by the city. Before the council makes any decision, Manning said he’ll suggest the city seek reaction from residents.

Colorado Springs’ two cemeteries pay for themselves through the sale of plots, making them the only two of their kind in the country, cemetery manager Will DeBoer said.

Cemeteries close all the time because they run out of space, DeBoer said, but that’s not always a bad thing; people can still visit them.

“The history doesn’t go away,” he said. “What you lose is the ability to bury a couple of generations in that cemetery.”

To some in Cripple Creek, that would be no small loss.

Laura Jeffery, 76, isn’t sure whether she wants to be buried or cremated. Either way, she hopes Mount Pisgah doesn’t close its gates to burials.

“It’s important for the history of the area that it stay open,” said the 30-year resident.

That’s especially true now that the city is starting a push to attract tourists based on history, she said.

As for Tremayne, he’s got unfinished business.

One day, he made a list of the things he’d like to see: the cemetery’s dirt roads named after the people who made the town what it is; replacing his wood markers on the graves of the unknown with metal ones so they’ll last forever; finding the rest of the hidden graves.

Most of all, Tremayne wants to be there every morning to open the gates and again at 5 p.m. to lock them.

He loves this cemetery, after all, and taking care of it keeps him from thinking about how much he misses his wife.

“It’s what keeps me going.”